Ted: ****/*****, or 7/10

These

last few years, bromance is the new key word in comedy movies.

The number of movies focusing on a bunch of guys, the closest of

friends, getting in and eventually out of trouble (often female

related) by being there for one another to the point they seem to

love each other more than they do their girlfriends, has been

steadily on the rise with no apparent end in sight. Of course, the

routine of the subgenre, all too firmly established by now, begs for

some variation. Enter Seth MacFarlane, the man behind the popular

animated sitcom Family Guy, who came up with an idea as simple

as it is effective, while appearing utterly ridiculous to the

uninitiated at first: replace one of the dudes by a living teddy bear

while otherwise staying true to the bromance formula. The

result, as both written and directed by MacFarlane, is a delightful

comedy film, that explores the boundaries of bromance by

wedging a fairly random element between the love affair of an

everyday guy and the girl he loves, an obstacle as male as the other

guys usually intervening in the natural progression of romance as

portrayed in this particular subgenre, but certainly not as human.

Despite Ted's abundance of effectively funny moments, it must

be said Macfarlane does stick to the bromance theme a little

too much, too often ignoring the fact we're watching a live stuffed

animal parading on the screen, instead concentrating on the way he

both hinders and helps the romance between his best buddy and his

girlfriend as if he were just a regular guy.

Applying

Patrick Stewart's ever reliable voice talent to the role of the

story's narrator, Ted opens on the unavoidable fantasy note

necessary to explain how a three ft. teddy bear came to life in the

first place. We're introduced to the protagonist, John Bennett, in

his past as the least popular kid on the block, a boy so generally

scorned other kids won't even bother to beat him up. To remedy his

isolation a little bit, John's parents give him a big plush teddy

bear for Christmas which instantly becomes his best buddy in the

whole world. Wishing the bear were alive, he quickly finds this

desire becomes reality, courtesy of a shooting star passing over at

the exact moment he made the wish. Despite his parents' initial

objections – they're freaked out by this talking toy, as any adult

would be – John can keep Ted and they grow up together. Of course a

live teddy bear is as extraordinary a thing in this movie's universe

as it would be in our own, and when discovered by the media, Ted

swiftly becomes a celebrity, only to fall into general acceptance and

eventual obscurity as his novelty wears off and people grow tired of

him. It doesn't matter for Ted, since he'll always have John, his

best friend for life; and as John grows up into a likeable, nerdy

adult (now played by Mark Wahlberg), Ted grows up with him into an

equally nerdy, grumpy know-it-all bear with a rather vulgar attitude.

These boys may have grown up together, but both of them have remained

immature, despite the fact John at least got himself a job and a

girlfriend, Lori (the ever charming and witty Mila Kunis).

Warning!

Spoilers! As is the standard problem the plot of most typical

bromance films offers, the main question for John in Ted

is how he can get serious in his relationship with Lori while still

being able to maintain his less than serious, and indeed kind of

childish, relationship with his oldest pal, if this is even possible

at all. As is the case with most regular guys, John picks romantic

love and the future it offers over brotherly love and staying stuck

in watching (bad) movies and smoking pot for ever: and so John

finally decides to move on with Lori, promising her to start acting

more responsibly and stop living the hedonistic life with his bear,

after he has helped Ted start a life of his own, living at a place of

his own and getting a job of his own, much to Ted's chagrin. If the

character of Ted wasn't a stuffed toy, there would be little

originality to this film's story. However, he is, which makes the

gags involving him applying for a workplace and hooking up with one

of his new colleagues all the more hilarious. Finally moving out of

John's place makes him less a guy and more a toy, underscoring the

silliness of having a teddy bear look for a job, hosting drunken

parties and abusing illicit substances, to great effect, resulting in

a string of memorable scenes that are sure to get those mouth muscles

moving in uproarious laughter, as is supposed to be MacFarlane's

forte.

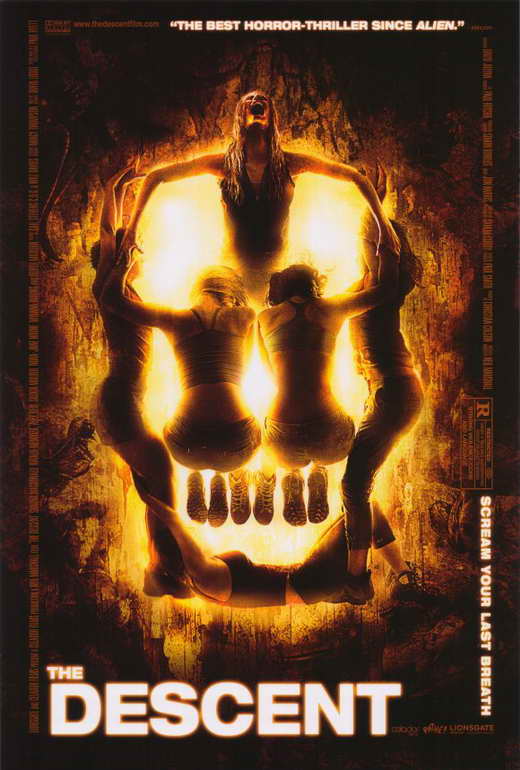

Unlike

the official poster of the movie – which features John and Ted

using the urinals, the latter holding a beer bottle – would have us

believe, Ted isn't driven solely by toilet humour,

illustrating definite heart and soul in its characters, human or

otherwise. On the other hand, it certainly isn't afraid to embrace it

either, walking an ever fine line between hilarious, sexually charged

witticisms and cheap, cringe worthy poop jokes: the film contains

both, but luckily the former prevails over the latter. Nevertheless,

such trash talk has become as much a staple of comedy over the last

few years as the other comedic element driving the humour in Ted,

which is the constant referring to celebrities or movies in an often

less than respectful tone. As is the case with most of MacFarlane's

work, Ted is laced with popcultural citations, varying from

the compulsory references to Star Wars to making fun of celebs

a lot of spectators will have a hard time remembering (I of course

know who Tom Skerritt is, but do you?). Quoted most often is Flash

Gordon (1980), a personal cult favorite of John's, and by

default, Ted's. Flash Gordon star Sam Jones gets to play

himself as a worn out movie star that has fallen into utter obscurity

(which isn't far from the truth), idolized by the pair of them, and

all too eager to get drunk and do a little too much drugs with them

(like I said, bromance), with dire consequences for John's

relationship with Lori, making her break up with him. This of course

also results into a conflict between Ted and John, which successively

ends up in an stupendously funny fight scene between the two of them.

However, when Ted afterwards gets kidnapped by a mentally troubled

man (the wonderful, underrated Giovanni Ribisi adding yet another

well performed but disturbing character to his diverse repertoire)

with a creepy fat kid – one of the few cases in the plot where

Ted's status as a living toy is of paramount importance instead of

negligible – John and Lori must reconcile to get their friend back,

at which point the movie adds some uncomfortable action scenes to the

overall piece, largely in detriment to the sense of comedy which

dominated the film up until this point. At least it's filmed in a

visually slick and fairly suspenseful fashion, keeping our mind off

the sudden lack of humour for a good fifteen minutes.

When it

comes to visuals though, Ted rules his movie. Being the product of

computer animation via motion capture and voice artistry, both done

by MacFarlane himself, the teddy bear looks and sounds as real as the

plot claims him to be. Though maybe not so intricate as Gollum or

King Kong, Ted is a rather impressive piece of CGI, at all times

making the viewer forget he's watching a bunch of pixels and feel

he's a real person when interacting with genuine actors. Given the

scale issues involved, that is quite an accomplishment for a director

who is unfamiliar with techniques and technology like this, but

obviously not with animation itself. It also helps MacFarlane has

assembled a fine troupe of actors to help him convince the audience.

Mark Wahlberg, who's often less than compelling in his performances,

does a surprisingly good job as a childish, nerdy guy even though he

does not look like one (which is a refreshing image to say the

least), visibly enjoying anything MacFarlane throws at him, including

the fight scene with the plush toy that ends with a television

crushing his genitals. As his opposite, Mila Kunis equally delivers

in her role of the beautiful and sensible girl who is truly in love

with John but who would desperately like to see him get rid of Ted,

without hurting him of course, so they can finally get serious for

real. MacFarlane's own performance as Ted completes the trio driving

this picture, and it's safe to say it's all for the best he took the

responsibility of breathing life into his own creation, despite also

carrying the burden of writing, producing and directing the film,

since few other actors would have understood Ted like he does,

successfully making the teddy bear both endearing and worth the

audience investing in him as a character, despite his often raunchy

and rude behavior.

However

accomplished a comedian and performance artist he may be, MacFarlane

proves he's less talented when it comes to the fantastic parts of the

movie. It isn't until the end of the movie, as Ted is accidentally

torn in half by his kidnapper, at which point Lori saves his

existence by wishing he was alive again, that we truly start to

question the logistics of the fantasy part of the plot. The film goes

out of its way to state how special a little boy's wish, made at

exactly the right moment in time, can be, but in the end it appears

everybody can make a teddy bear come alive when coincidence takes

over (it's a little too convenient from the audience's perspective to

attribute the circumstances to fate alone). It makes you wonder why

Ted is the only living toy around in MacFarlane's world, since the

desire to make toys come alive has tormented children for centuries.

Though in the end it doesn't truly matter how Ted came to be what he

is, MacFarlane's haphazard writing in this regard only hurts the

plot's credibility. It might have been preferable if MacFarlane

ignored the exact how-and-why of Ted's existence altogether, even

though that too might have raised uncomfortable questions in the

audience.

Overall,

as a comedy Ted is largely successful, despite the fact its

most stand-out feature – Ted himself- is not the driving force

behind the film's plot. While Ted is naturally a key component, it's

still all about John, and the story revolves around his attempt of

balancing his life with Ted and his love for Lori equally. Therefore,

Ted is less about a live teddy bear trying to cope with the

real world and more about a guy trying to make room for the love of

his life while still aiming to keep in touch with his best friend as

much as he would like to. In this regard, bromance wins over

“bearmance”, though the audience would have loved to see more of

Ted's life on his own and his status as a washed-up celebrity which

in many respects deliver the most moments of hilarity. Maybe the

story would have been better off if the roles were reversed and Ted

was the protagonist instead of John, realizing you can't stay

immature together for ever and at one point, even as a living toy,

you just have to move on with the woman you love and loosen your

relationship with your best buddy a bit. Considering Ted's

happy ending (mostly for John and Lori) leaves ample room for Ted's

character to be further developed on his own, it's not unlikely we'll

be seeing more of him in the near future, also taking into account

Ted is doing huge at the box office, mostly because of the

lack of other appealing movies available for viewing in theaters at

the moment. 2012 witnessed a great movie summer, with the promise of

an equally great finale in its last few months, but the period

in-between is plagued by a shortage of films appealing to a wide

demographic, except for this one; it will come as no surprise Ted

2 is already a work in progress, and hopefully a sequel will give

Ted his due: after all, despite the charms of this introductory

piece, it's not truly about the teddy bear, though we obviously like

to see him the most. Maybe we can trade in Mark Wahlberg for Sam

Jones altogether for the next film? After all, you can't keep true

bromance down.

And

watch the trailer here: